Legal Experts Warn of Dangerous Precedent as Scholars Defend Kendrick Lamar’s “Not Like Us” Diss in Drake Lawsuit

The ongoing legal battle between Drake and Universal Music Group (UMG) over Kendrick Lamar’s chart-topping diss track “Not Like Us” has taken a new turn as four legal scholars have filed an amicus brief in support of UMG’s motion to dismiss the rapper’s defamation lawsuit. The scholars argue that treating rap lyrics as literal statements in a court of law not only undermines artistic expression, but also sets a dangerous precedent that could stifle creativity and deepen racial bias in the judicial system.

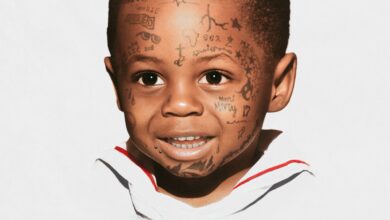

Drake filed the lawsuit earlier this year, alleging that UMG promoted the track in a way that defamed him and damaged his brand. One of the most controversial lines in Kendrick’s diss labels Drake a “certified pedophile,” a lyric that the Toronto artist claims is both false and defamatory. However, the scholars emphasize that diss tracks — especially in hip-hop — have long relied on hyperbole, exaggeration, and stylized bravado as a means of creative competition rather than factual accusation.

“Drake’s defamation claim rests on the assumption that every word of ‘Not Like Us’ should be taken literally, as a factual representation,” the scholars wrote, according to AllHipHop. “This assumption is not just faulty—it is dangerous.”

Their brief asserts that hip-hop diss tracks follow a unique artistic tradition that prizes clever insults, verbal combat, and metaphorical storytelling. The lyrics, they argue, are meant to entertain and provoke, not to serve as legal statements or factual declarations.

“They are hyperbolic forms of creative expression consistent with the unique artistic practices and normative conventions of the genre,” the group explained. “Rap diss tracks are understood by audiences not to represent factual assertions about the opposing artist, but rather to demonstrate skill and dominance meant to build allegiance and win competitions through clever wordplay, hyperbole, bluster, and demonstrations of disrespect.”

Beyond the implications for music, the scholars warn that allowing such lyrics to be used as literal evidence could have far-reaching consequences for free speech and racial equity in the courtroom. They cite studies showing that rap lyrics are disproportionately weaponized against Black artists in legal cases, often reinforcing harmful stereotypes.

“When rap lyrics are admitted, it is because they are treated as literal. This in turn opens the door to racial bias and stereotypes into the courtroom, as empirical studies have demonstrated,” the brief continues. “Treating rap lyrics as literal also threatens First Amendment speech protections, and the practice already has created a demonstrable chilling effect across the industry.”

UMG has also defended itself in court by describing the song’s lyrics as “nonactionable opinion and rhetorical hyperbole,” arguing that the song is protected under the umbrella of artistic expression. The company denies any coordinated effort to harm Drake’s reputation and insists that the success of “Not Like Us” was driven by public interest, not industry manipulation.

Drake filed the lawsuit in January, shortly before Kendrick Lamar’s explosive Super Bowl LIX appearance, claiming that the release and promotion of the song were part of a calculated effort to damage his public image. His complaint centers on the track’s highly inflammatory lyrics, which he says amount to defamation.

As the legal showdown continues, the outcome of this case could carry serious implications for how courts interpret music — especially in genres like hip-hop, where lyrical exaggeration is a cultural cornerstone. With the support of legal experts warning against literal interpretations of rap lyrics, the case is fast becoming a critical flashpoint in the intersection of music, law, and free speech.